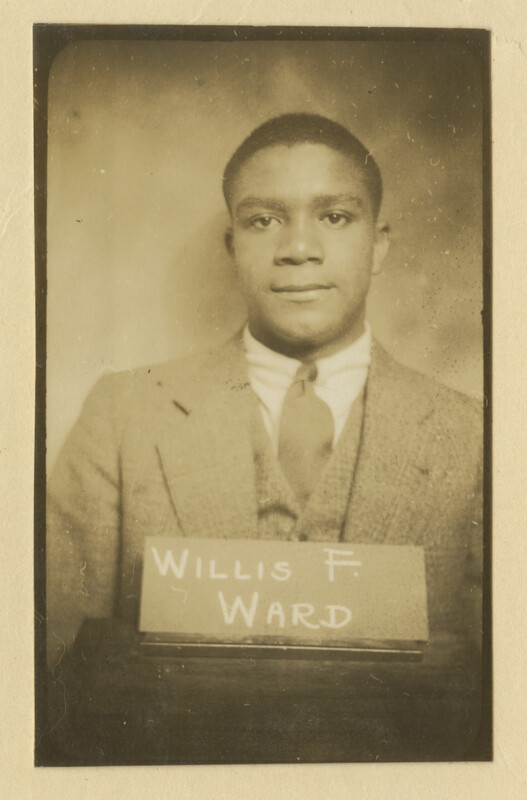

A Mixed Welcome

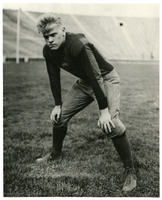

First Impressions

Ward generally received a warm welcome from other athletes when he arrived. A number of them went out of their way to acknowledge him. When Ward first went down to the Field House to get his locker assignment, he was met by Bob Miller, captain of the swimming team and the son of Judge Guy Miller. He said to Ward, “I’m Bob Miller. My father told me you were coming and if you have any problems, let me know.”

Kipke had apparently asked a few football players to make sure Ward felt welcomed. Ivan Williamson, star end and future 1932 team captain, approached Ward and said, “Welcome to the Michigan team. Any time I can help you, let me know. If you have any problems with anybody, let me know, because we’re prepared to take care of them.”

A fellow freshman football player, Gerald Ford, also extended a kind greeting. Ford, whose parents chose to send him to integrated Grand Rapids South High School, was an all-city player and doubtless well aware of Ward's reputation. On spying Ward at registration in the Waterman Gymnasium, Ford stepped up and introduced himself, starting a relationship that would take on greater significance several decades later.

In later interviews, Ward recalled no racial incidents with his fellow athletes. When they left the apparent camaraderie of the playing field, however, Ward and his white teammates returned to a largely segregated campus and city.

A Home on Campus

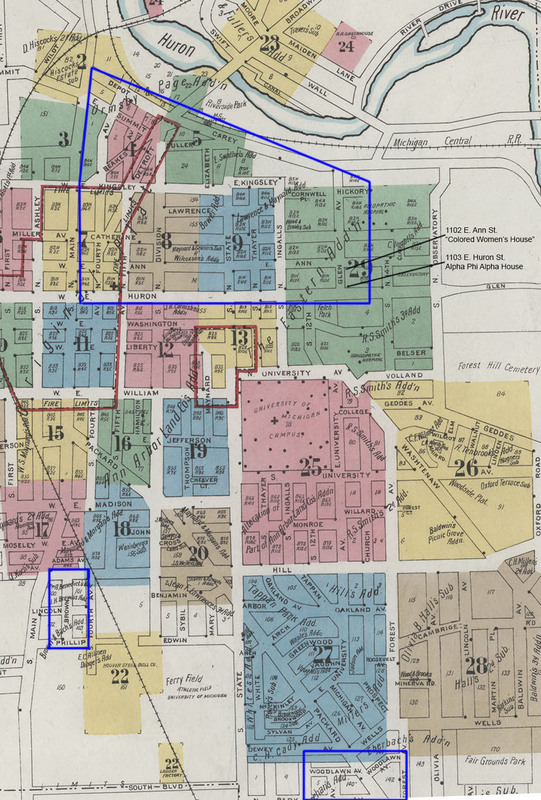

The 1930 U.S. Census recorded 940 African Americans living in Ann Arbor, making up about 3.5 percent of the city’s population. The Black community was concentrated in what was known as the “Old Fourth Ward,” an area north of campus, bounded by what today is the University of Michigan Medical Center on the east, Kerrytown on the west, and running north from Huron Street toward the railroad tracks along Fuller and Depot streets.

Restrictive covenants in deeds, redlining by lenders and real estate agencies, and unofficial agreements and customs excluded African Americans from living, owning property, or renting in many parts of the city. Even some of the city lots that would become Michigan Stadium were covered by racially restrictive covenants that specified "nor shall this lot nor any building thereon, be sold or leased to or occupied by any colored person or any club, society, or corporation of which colored persons are members." This was standard language in many deeds and, if interpreted literally, would have prevented Ward from taking the field.

In 1948, restrictive covenants were declared unconstitutional and unenforceable by the U.S. Supreme Court in Shelley v. Kramer.

There was no University housing for men (that would not come until the West Quad dormitory was built in the late 1930s). There were dormitories for women, including Martha Cook, Helen Newberry, and Mosher-Jordan Hall. Black women were largely excluded from the dormitories. In 1930, the University established and ran a house for “colored girls” at 1102 East Ann Street, where all Black female students were encouraged to live and which continued to operate well into the 1940s. Nevertheless, Black women were actively fighting at that time for the right to live in the University’s dormitories.

Black residents of the city rented out extra rooms or ran boarding houses catering to Black students. The office of the Dean of Women maintained lists of approved off-campus houses, including designated houses where Black students were welcome.

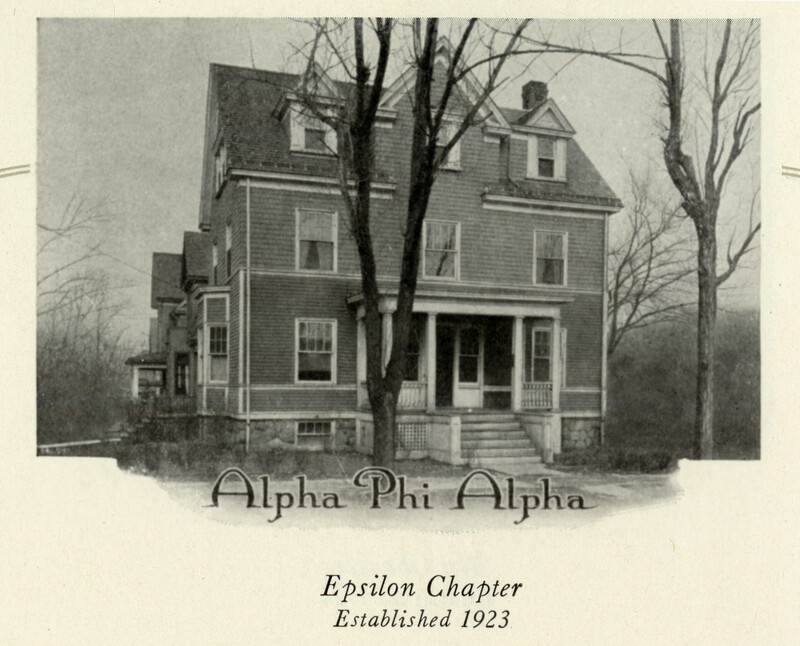

For Black men, fraternities became a vital part of the college experience. Excluded from the white fraternities on campus, Black students established chapters of historically Black fraternities.

In 1909, the Epsilon chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha was established at Michigan; founded at Cornell in 1906, it was the nation's oldest Black fraternity. The Phi chapter of Omega Psi Phi was chartered at Michigan in 1921, followed by the Sigma chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi in 1922; both fraternities were established in 1911.

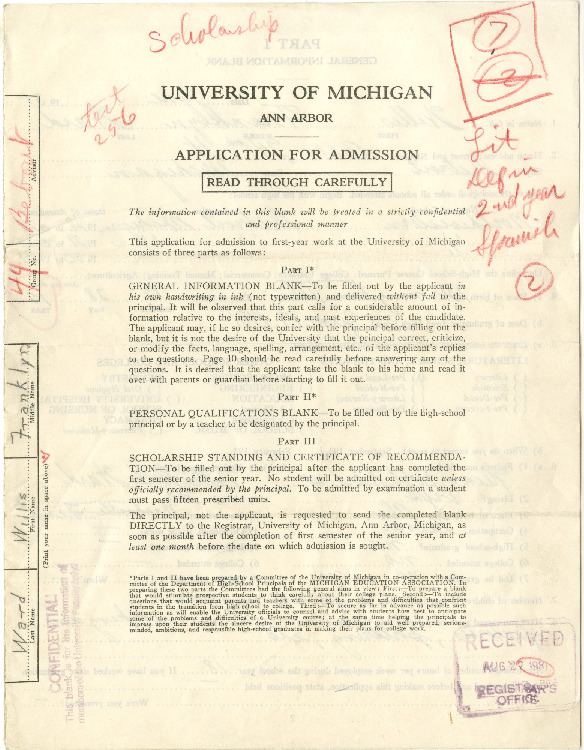

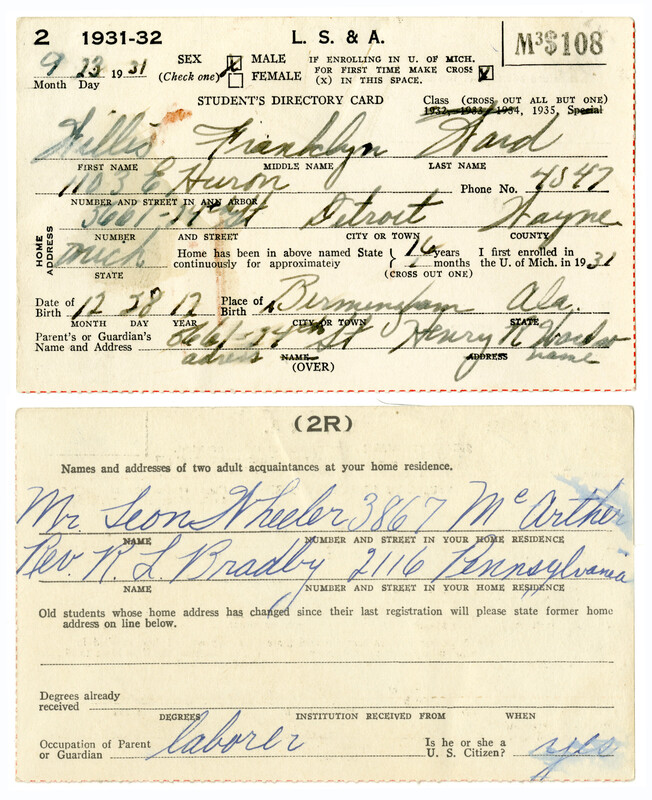

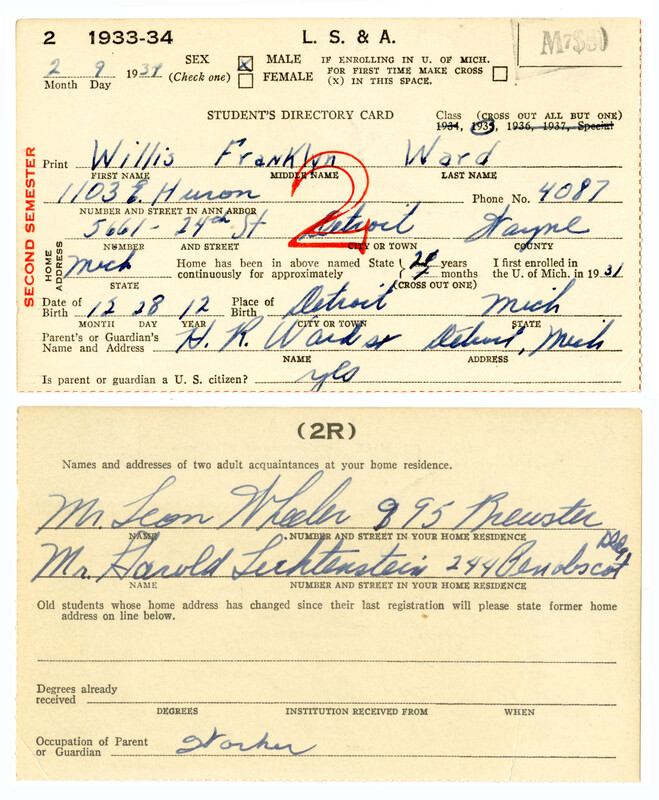

Because they could not afford to own their chapter houses, Black fraternities were often not recognized as part of the Pan-Hellenic fraternity system. Nevertheless, the house where the majority of the Alpha Phi Alpha members lived, at 1103 East Huron Street (near where the Power Center for the Performing Arts now stands), became a focal point of Black campus life. It was the site of dances and other social gatherings, and frequently hosted visiting Black speakers and musicians. Ward pledged to Alpha Phi Alpha as a freshman and lived in the Alpha house for most of his college career.

Historian John Behee’s interviews with Black athletes from the 1920s and 1930s confirm the largely segregated social worlds. All commented that Black students rarely took part in the big social events on campus.

William DeHart Hubbard, the 1924 Olympic gold medalist in the long jump, noted, “They would have the big—what you call it—the 'J-Hop' or something, and we just wouldn’t bother with them.”

Ward himself said, “It was lonely, lonely as hell,” when recalling the small number of Black students on campus. In a later interview with David Pollock, Ward was prompted to recall his relationship with Gerald Ford. Ward said that while by chance they had never had class together, they would frequently see each other in passing on campus. That they apparently did not socialize outside of athletics is less a characterization of their friendship than of the segregation on campus at the time.

Community

For much of the 20th century, Ann Arbor's African American community was concentrated in the Old Fourth Ward neighborhood, roughly outlined in blue in this 1925 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map. Many Black students boarded with families or in apartment houses on Glen Avenue and Kingsley, Beakes, Catherine, and Ann streets.

The 100 block of Ann Street was the center of the Black business district, hosting a changing roster of cafes, barbershops and beauty salons, shoeshine businesses, professional offices, and pool halls. Around the corner on North Fourth Avenue, the Colored Welfare League had purchased several buildings and rented rooms to boarders and storefronts to businesses, and provided space for community organizations. Also located there was an early incarnation of the Dunbar Center, a social and service hub for several generations of U-M's African American students. Bethel A.M.E. Church was located at 632 North Fourth Avenue.

Several other pockets of Black and mixed-race residences developed south of campus, including around Hill and Green streets and Woodlawn and Sheehan avenues.

Sources: John Behee, Willis Ward, Football, 1932–1934; Track, 1933–1935 [interviews], 1970; Owen W. Bombard, The Reminiscences of Mr. Willis F. Ward [interview], 1955; John Richard Behee, "Fielding Yost's Legacy to the University of Michigan" [dissertation], 1970; John Richard Behee, Hail to the Victors! Black Athletes at the University of Michigan, John R. Behee; Tyran Kai Steward, "In the Shadow of Jim Crow: The Benching and Betrayal of Willis Ward" [dissertation], 2013; Willis Ward, "Willis Ward Says the Alumni Prevailed Upon Jerry Ford to Play in the Georgia Tech Game" [interview for 1976 Ford election campaign], n.d.; David S. Pollack, Willis Ward [interview], 1983; The Michigan Daily; Willis Ward Alumni File, Bentley Historical Library; Board in Control of Intercollegiate Athletics records, Bentley Historical Library; Brian A. Williams, "An Unwritten Law," 2017; Donald R. Deskins, "Negro Settlement in Ann Arbor" [master's thesis], 1962; James Tobin, "Lonely as Hell," 2019; Ann Arbor District Library website.