A One-Man Track Team

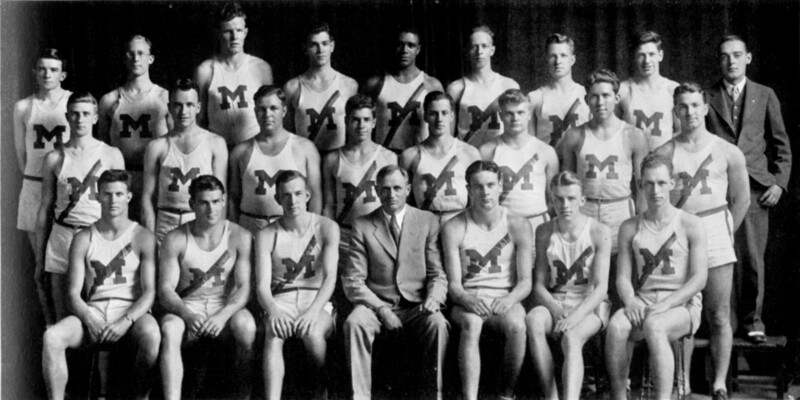

Freshman

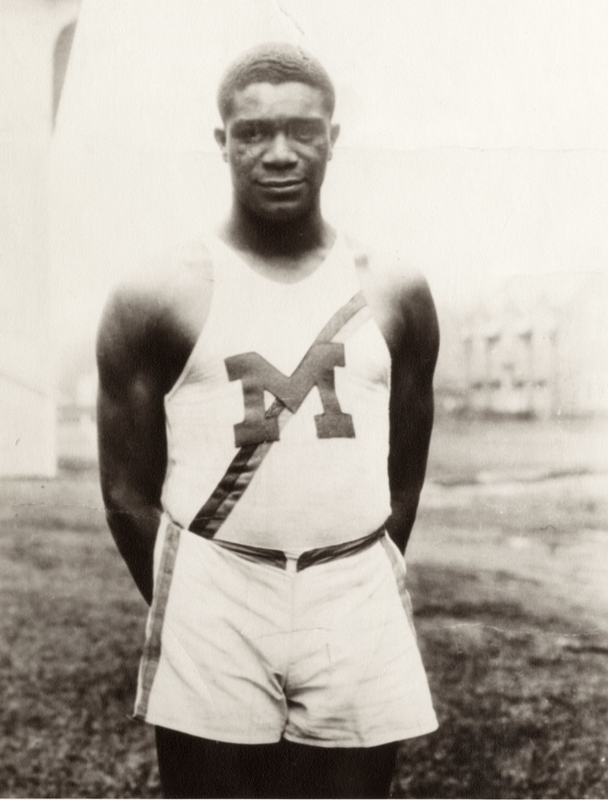

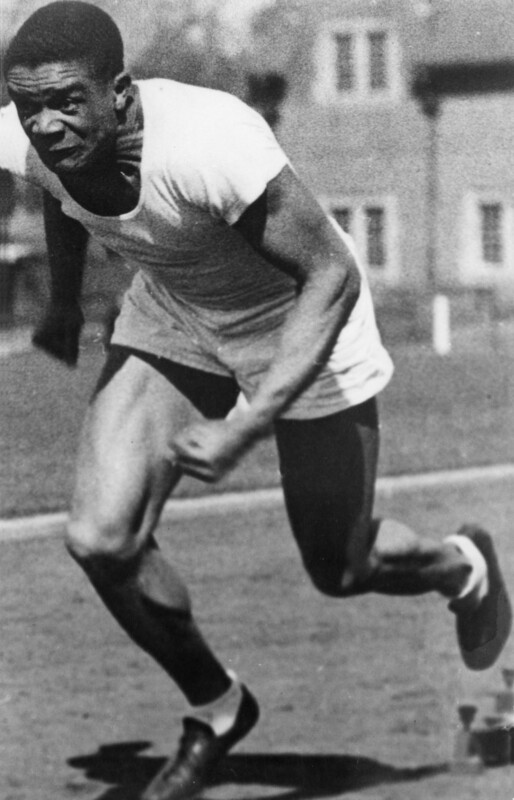

When freshman Willis Ward reported for coach Charles Hoyt’s track practice team in December 1931, he had already high-jumped higher than any Wolverine and run the hurdles nearly as fast as the best U-M athletes. In the short sprints, he was second only to fellow Detroiter Eddie Tolan, who would win two gold medals at the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles.

As a freshman, Ward was ineligible to compete in varsity meets. But he was invited to participate in the high jump at the NCAA championship meet in Chicago, which was a qualifying meet for the U.S. Olympic trials. He posted the highest mark, at 6 feet 7-1/2 inches.

Sophomore

In his 1933 varsity debut, in a dual meet with the University of Chicago, Ward won the 60-yard dash in 6.2 seconds, tying the conference and world records, and won the high jump with a leap of 6 feet 5-3/8 inches, which tied Chicago’s field house record. At the conference indoor meet, he won the high jump and placed second in the 60-yard dash.

Twice he placed second to Marquette’s Ralph Metcalfe, who had won two silver medals behind Tolan at the Los Angeles Olympics. Ward trailed just behind Metcalfe in the 70-yard dash at the West Virginia Relays and in the 100-yard dash at the Drake Relays.

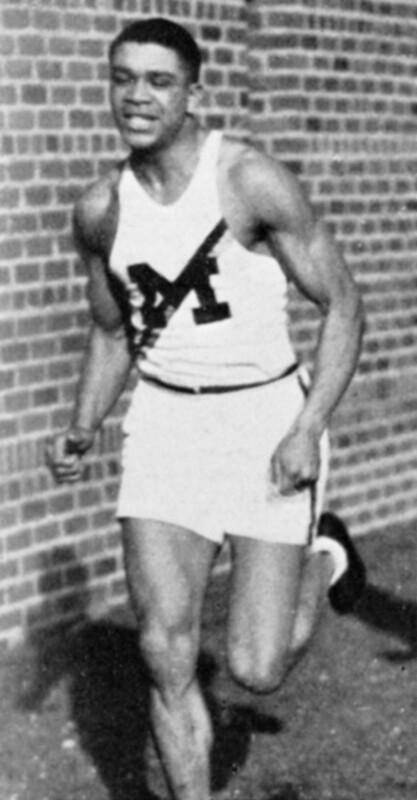

At the conference outdoor meet, Ward won the 100-yard dash and high jump and finished second in 120-yard high hurdles and broad jump, leading U-M to the conference title. Sportswriters dubbed him "The One-Man Track Team." Ward placed third in the high jump and seventh in the long jump at the NCAA meet, helping Michigan to a fifth-place team finish.

Junior

Ward opened the 1934 season by sweeping the 60-yard dash, high hurdles, and high jump in five indoor meets. He repeated the feat at the conference championships, solidifying his reputation as a “one-man track team.”

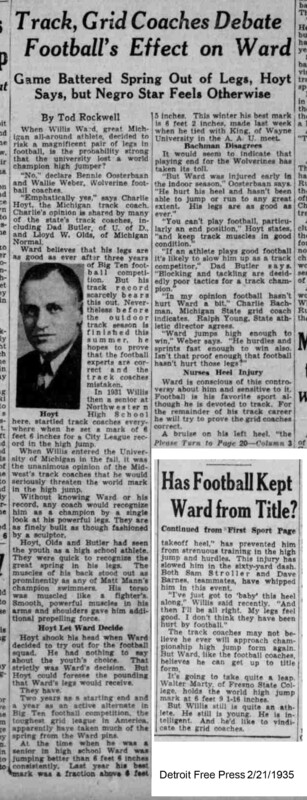

At the outdoor championships, Ward was predicted to take four firsts, but a pulled muscle in the 100-yard dash ruined his chances. He salvaged a first place in the broad jump and a fourth in the high jump.

Senior

The 1935 season started well, with Ward taking three firsts at the state Amateur Athletic Union meet. In his first matchup against Jesse Owens, Ward beat the sensational Ohio State sophomore twice, taking the 60-yard dash in 6.2 seconds and 60-yard high hurdles in 8 seconds flat—a Yost Field House record. Owens got his revenge three weeks later at the conference meet, tying the world record at 6.1 seconds with Ward in third place behind teammate Sam Stoller.

Michigan made a highly publicized trip west to face University of California-Berkeley in early April. Ward took firsts in the high hurdles, broad jump and high jump, and second in the 100-yard dash. Despite Ward's efforts, the Golden Bears won the meet 75-1/2 to 54-1/2.

Injuries kept Ward out of the next three meets, and he was still ailing for the conference meet at Ferry Field—enough that he passed on the 100 and high hurdles. He managed a tie for first in the high jump and placed second in the broad jump.

Owens was the sensation of the meet, setting world records in the 220-yard dash (20.3 seconds), 220-yard low hurdles (22.6 seconds), and broad jump (26 feet 8-1/2 inches), and tied the record in the 100-yard dash (9.4 seconds). In the long jump, Ward uncorked the best leap of his career, 25 feet 1-1/2 inches, still finishing more than a foot and a half behind Owens. Ward’s points were crucial to giving Michigan the team title over the Buckeyes, 48 to 43-1/2. At the NCAA meet at Berkeley, Ward finished in a three-way tie for second in the high jump and fourth in the long jump.

Ward came in just ahead of his friend Owens in an incident arising from a Jim Crow custom both had faced before. As Ward recalled, when Michigan arrived at its Indianapolis, Indiana, hotel for the 1935 Butler Relays, the clerk told Hoyt that Ward would not be allowed to stay with the team and instead would have to board with a local Black family.

The coach insisted that unless Ward stayed with his teammates at the hotel, Michigan would pull out of the meet. After consideration, the hotel relented—much to the surprise and delight of the Black bellhops and maids. When Ward got to his room, he immediately called Owens to tell him “I’m in,” and that Owens had better get his coach to follow Hoyt’s example. Not long after, Owens returned the call: “I’m in, too.”

In telling the story for John Behee’s interview, Ward clearly relished not only getting the jump on Owens, but more importantly the role he and Hoyt had played in ending a racist custom—at least at one hotel, for one meet. But in interviews with both Behee and David Pollock, Ward recalled a similar incident in Chicago when Kipke insisted he would stay with the football team.

Much like his final football season, Ward’s last year on the track was a bit of a disappointment. The injuries and the lingering psychological effects of the Georgia Tech benching had taken a toll. Some, including Hoyt, felt the pounding Ward had taken in football had hurt his track performance. Ward, however, never second-guessed his commitment to play football.

Sources: Athletic Department records, Bentley Historical Library; John Behee, Willis Ward, Football, 1932–1934; Track, 1933–1935 [interviews], 1970; The Michigan Daily, Michigan Alumnus, Detroit Free Press.