Campus Jobs and Social Life

Washing Dishes

There were no athletic scholarships and, like most students, including athletes, Ward needed to work to help pay his way. His freshman year, Kipke arranged a job for him as a dishwasher at The Parrot restaurant, at 338 South State Street (now the site of Ashley’s).

Ward recalled: “The cook happened to be a Black man and, because I was going to be a football player and he loved me, he fed me better than anybody. I ate really well for about a month. Because it was known that I was a kid from Northwestern who was a world-beater, when I would go in, the kids would speak to me. The owner thought this was out of step with the times, so he told the chap who was managing it to tell me to use the back door.”

Ward told Kipke about the situation. “The next day he got me a job washing dishes at the Michigan Union. I was the first Black kid to wash dishes at the Union.” An hour of work would get him a free meal. A job at the Union was considered a plum position for athletes, usually reserved for upperclassmen.

Kipke also helped Ward get a job at Van Boven Clothing, which still operates on State Street; he would go in to clean up three days a week—enough to pay his rent.

Finding a Voice

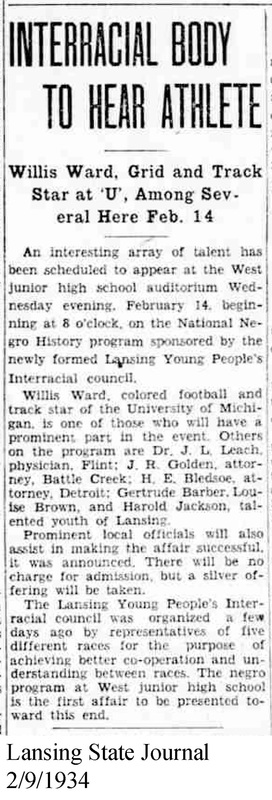

Ward’s prominence as an athlete led to his participation in two public forums addressing questions of race and the status of African Americans. He was a featured speaker at a February 14, 1934, event hosted by the Lansing Young People’s Interracial Council, which had been organized by representatives of five racial groups to promote understanding and cooperation. Other speakers included prominent lawyers J.R. Golden of Battle Creek and Harold E. Bledsoe of Detroit, local professionals, and Council members.

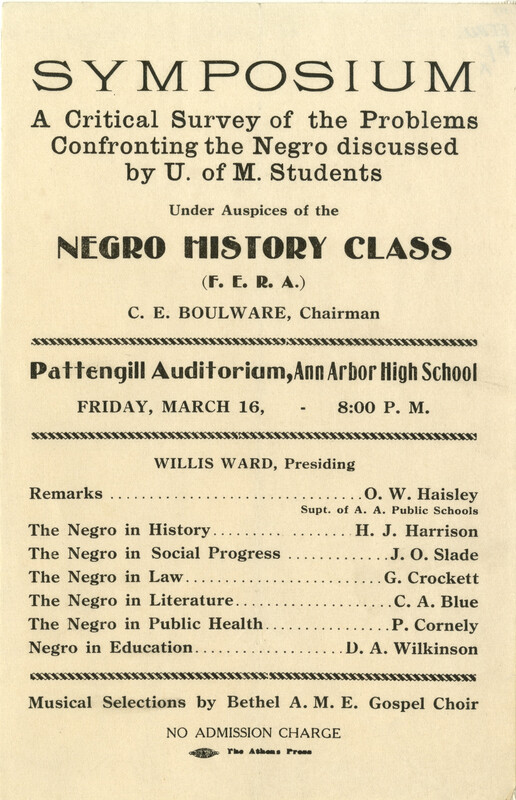

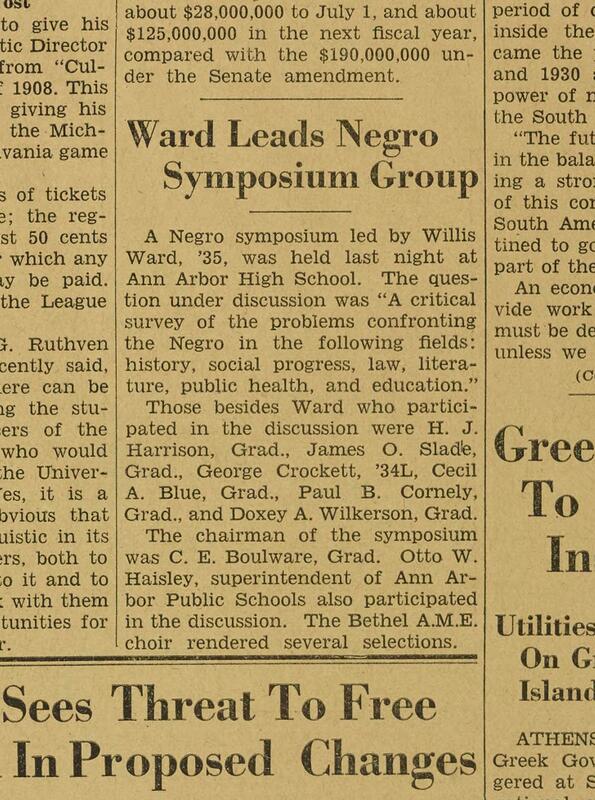

A month later, on March 18, Ward presided at a symposium at Ann Arbor High School concerning “Problems Confronting the Negro” in the areas of history, social progress, law, literature, public health, and education. The symposium was organized by U-M African American graduate students, including several of Ward’s fraternity brothers, under the auspices of The Negro History Class, a local effort sponsored by the Depression-era Federal Emergency Relief Administration.

Among the other speakers were U-M law student George Crockett Jr., who went on to a distinguished career as lawyer, judge, and member of Congress; and Doxey Wilkerson, a graduate student in education who would be dismissed from the University for Communist Party affiliations, but who went on to a notable academic career at Howard and Yeshiva universities. O.W. Haisley, superintendent of Ann Arbor Public Schools, provided comments.

Even if Ward’s primary contribution to these events may have been his prominent name, it indicated a willingness to take a small step into activism.

Sphinx and Michigamua

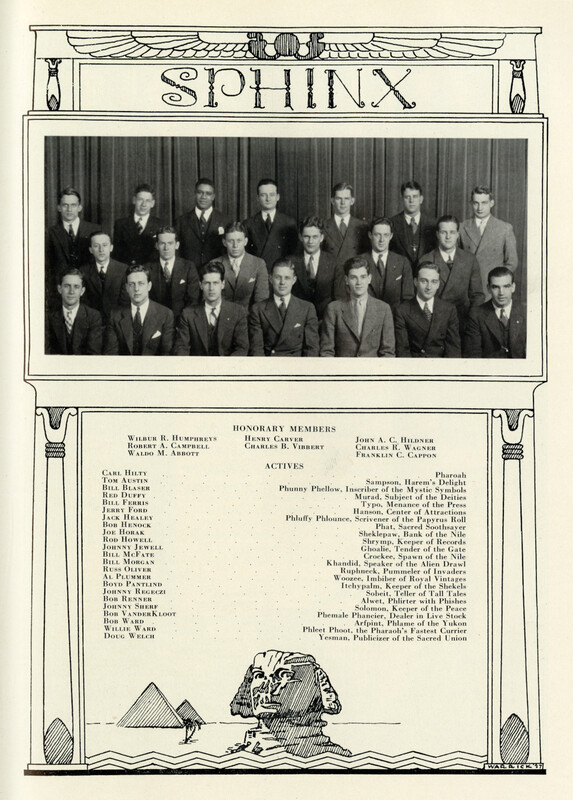

Sphinx and Michigamua were, respectively, the junior and senior class honorary societies—self-selected groups of the “leaders” on campus (which, of course, meant men). Ward was tapped to join Sphinx in the 1933–34 school year—the first African American to join the group. Michigan Daily writer Al Newman noted Ward’s selection in his May 23, 1933, “Play-By-Play” column.

Of the 12 sophomores so honored, Newman wrote, “his selection is especially significant in that he is the first member of his race to be taken into an honorary society at Michigan. We feel that Ward is deserving of the honor bestowed upon him, not only because he is an athlete of unquestionable ability, but because he is an all-around ‘regular guy.’ Unassuming, in spite of his athletic fame, he is well-liked by all who come in contact with him.” Sphinx members were given faux “Egyptian” names: Ward was dubbed Phleet Phoot, the Pharaoh’s Fastest Courier.

Sphinx and Michigamua both had a number of reserved spots for editors of The Michigan Daily and Michiganensian, captains or managers of the major sports teams, and other campus figures.

At the time, typically 75–80 percent of Sphinx members would be tapped for Michigamua the following year. Ward would not be among them.

Michigamua had never had a Black member, and would not until Gene Derricotte and Charles Fonville joined in 1949. In fact, Michigamua members played a role in disrupting a rally in support of Ward on the eve of the Georgia Tech game.

Sources: John Behee, Willis Ward, Football, 1932–1934; Track, 1933–1935 [interviews], 1970; The Michigan Daily; Michiganensian; Lansing State Journal; Alumni Files-Willis Ward.