Game Day

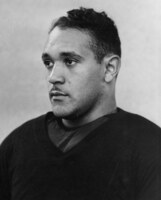

As game time arrived on October 20, it was a certainty Willis Ward would not be in uniform or on the sideline, despite the absence of an official statement from the Athletic Department. There was still some question as to where Ward would be or what he might do.

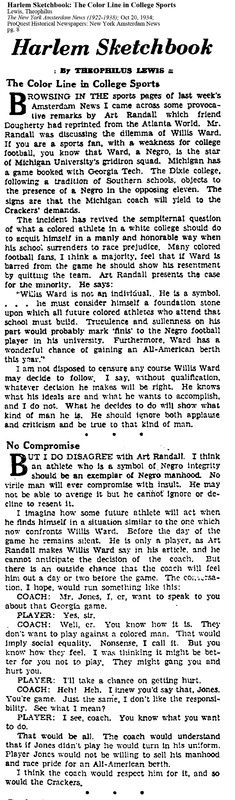

For weeks, Ward had been under pressure from all sides: to make a bold stand against prejudice and quit the team; to follow his coach’s orders; to consider the good of the team; to weigh the chance he could be intentionally injured; to calculate his own long-term interests. The pressure came from family and friends, from supporters and opponents on campus, from opinion columns and letters in the Black press, and from within. He was accused of cowardice for not publicly challenging his coach’s decision, and defended for accepting it.

Various press accounts of the game placed Ward in the stands, in the press box, or at his fraternity house. There was even a rumor he had been out of town to scout an upcoming opponent. The Athletic Department supposedly did not want Ward to watch the game from the stands, lest he become the focus of a protest.

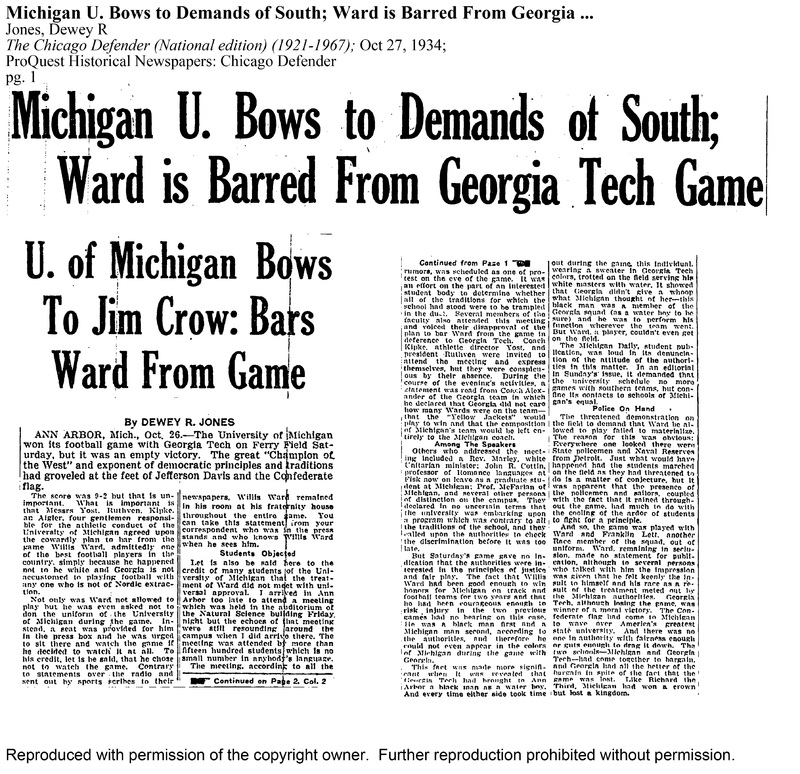

Arrangements were made for him to be in the press box, and it was widely reported that Ward watched the game there. However, Dewey Jones (B.A., 1922), who covered the game for the Chicago Defender, wrote that “a seat had been provided for him in the press box and he was urged to sit there and watch the game if he decided to watch it at all. To his credit, let it be said that he chose not to watch the game at all. Contrary to reports over the radio and sent out by scribes to the newspapers, Willis Ward remained in his room in his fraternity house throughout the game.” Ward would later confirm he listened to the game on the radio at the Alpha Phi Alpha house.

Sophomore Franklin Lett, a reserve tackle who had not seen any action that season, was also banned from the game for being Black. In his January 3, 1934, letter, Georgia Tech coach Alexander had insisted Michigan must leave “Ward, or other negro players, on the sideline,” but it is unclear if school officials were aware that Lett was on the Michigan team. Like Ward, there was some dispute over his whereabouts during the game. Some reporters placed Lett on the sideline; others said he was banned from the stadium. It is possible he listened to the game with his fraternity brother Ward.

After the 1934 football season, Lett was not invited to try out for the varsity basketball team. A year earlier, Michigan had given in to protests from the NAACP and Black alumni and permitted Lett to play on the freshman team. Coach Franklin Cappon, however, was not about to challenge the “gentlemen's agreement” and allow Lett on the varsity squad. Lett participated in spring football practice and was invited to practice by Kipke in August, but did not return to school.

A Dreary Affair

The game itself was a dreary affair, played in a steady rain in front of fewer than 21,000 fans (only two home games would top 30,000 attendance in 1934). The feared protest didn’t materialize—some cited the weather, although Chicago Defender reporter Jones noted the heavy presence of the Michigan State Police and U.S. Naval Reserve members from Detroit. It is also possible that support for the Ward Committee was not that wide or deep among the student body.

Ted Savage started in Ward’s place at right end.

As he had first proposed back in January, Georgia Tech coach W.A. Alexander held out his star end Charles “Hoot” Gibson as compensation for Kipke benching Ward. Gibson was apparently informed he would sit shortly before game time, he is listed in the printed starting lineup, and reportedly remained bitter over his benching for the rest of his life.

Michigan scored the game’s only touchdown on a 60-yard punt return by Ferris Jennings. Willard Hildebrand kicked the extra point, a chore Ward would normally have handled. The only other scoring on the muddy field was a safety by each team. The 9–2 victory would be Michigan’s only win for the season.

Reporting on the game in much of the white popular press barely took notice that Ward had been benched. Michigan Alumnus rather delicately observed that “Ward refrained from playing out of deference to the Southerners. To compensate, coach Bill Alexander asked his star end Gibson to remain on the sidelines." Georgia Tech Alumnus coverage noted, “The Jackets played without the services of Hoot Gibson, stellar end, who was held out by agreement with Michigan, who was not using Ward, negro end.”

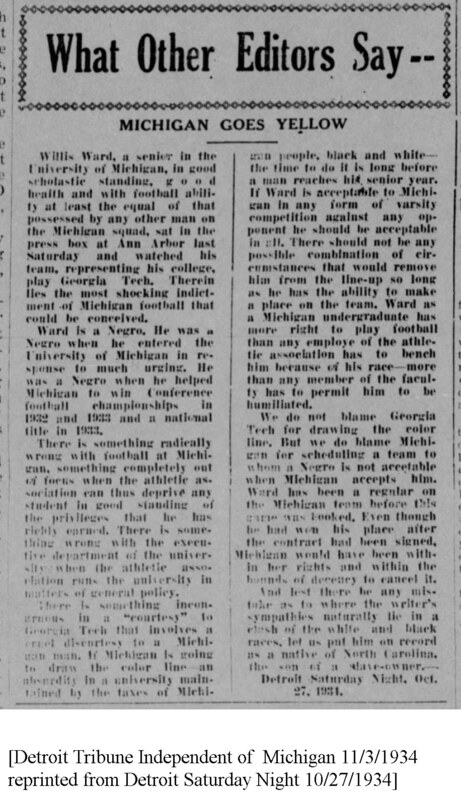

In the Black press, Michigan was excoriated for caving to Jim Crow. To quote Jones again, “The great ‘Champions of the West’ and exponent of democratic principles had groveled at the feet of Jefferson Davis and the Confederate flag.” The Pittsburgh Courier labeled the game without Ward “a stinging and bitter insult” that would mar the University’s reputation for years.

Postgame and Ward’s Spirit

Neither the Athletic Department nor the University would make a public response to the criticism after the game. Fielding Yost's only comments on the affair came in letters to coaches W.A. Alexander and Dan McGugin.

In a December 12 letter concerning the financial settlement for the game, Yost offered an apology of sorts to Alexander. “I never dreamed there would be so much agitation about the matter. The agitation was developed by a committe of five Jewish sophomore students, four of them from New York City, one from Michigan. They did it in the name of the United Front Committee on Ward.”

In a private letter to his brother-in-law McGugin, Yost reflected on the game with a self-satisfied tone: “The Michigan Georgia Tech game is now one of history. You cannot realize the effort that was made by colored organizations and local radical students to create trouble. Their slogan was, WARD PLAYS OR THE GAME MUST BE CANCELLED. The colored race must be in a bad situation judging from the number of national organizations organized to ensure racial equality or no racial discrimination. ... There was not a chirp from anyone, nor was there any disturbance of any kind at the game. The spirit was fine and the attitude of the crowd was excellent.”

Willis Ward’s spirit was not so fine. Friends reported that “he felt keenly the insult to himself and his race as a result of the treatment meted out by the Michigan authorities.” Ward would later testify to the lasting impact the benching had on him as an athlete and an individual. “It was wrong and it will always be wrong. And it killed my desire to excel.”

In a 1983 interview, Ward reflected on the Georgia Tech game: “I said, well, I will go through the motions and play this season, and get my degree and go about my business and try to get a law degree and practice law.”

The Michigan Daily's editorial position on the Georgia Tech affair had vacillated in the days leading up to the game: in some cases sympathizing with Ward, in others supporting the Board in Control and the right of coaches to manage athletic affairs without interference, consistent only in its criticism of the more radical elements among Ward's supporters. In its postgame summary, the Daily again temporized on the central question, and concluded “it was the peculiar characteristic of the Ward–Georgia Tech matter that everyone who touched it did so only to lose in respect and esteem.”

Many of the letters and telegrams protesting the decision to bench Ward were addressed to University President Ruthven, and some held him personally responsible for condoning the decision and for the resulting damage to the University's reputation. Ruthven had delegated all responsibility in the matter to the Board in Control, and made no public comment at the time.

But in an October 12, 1934, letter to Shirley W. Smith, secretary of the University, Ruthven wrote, “My life is being made miserable by the colored brethren. ... I wish now, in some ways, that I had taken the Ward matter into my own hands.” He took no action in that week before the game, but was concerned about the fallout, concluding, “the Board in Control has not handled the situation well and I am afraid we are in for some embarrassment.” Ruthven certainly did not reach out to Ward or Lett, even though he was known to stop in at residence halls and chat with students, and was said to be “always ready to advise a student with troubles.”

Sources: Board in Control of Intercollegiate Athletics records, Bentley Historical Library; Athletic Department records, Bentley Historical Library; Ralph Aigler Papers, Bentley Historical Library; The Michigan Daily; Michigan Alumnus; Georgia Tech Alumnus; Michiganensian; ProQuest Historical Newspapers; Newspapers.com; Peter E. Van de Water, Alexander Grant Ruthven of Michigan: Biography of a University President, 1977.