A Henry Ford Protégé

Henry Ford and the Black Community

Henry Ford and the Ford Motor Company had a complex relationship with Detroit’s Black community. Ford was by far the largest employer of Black workers in Michigan and, to many, he was a hero for having opened employment and advancement opportunities.

Willis Ward’s father and several of his stepbrothers worked in Ford plants. When the company began hiring African Americans, Rev. Robert L. Bradby of the city’s Second Baptist Church (the Wards’ home church) and other prominent ministers served as virtual personnel agents for Ford. A character reference from one of the ministers was practically a requirement for a Black person to get hired at the company. Ford himself contributed funds to Black churches, the Detroit Urban League, and other community organizations, sometimes providing substantial portions of their budgets. This gave him significant leverage with the African American community.

To others, especially those who supported union organizing efforts by the Congress of Industrial Organizations and United Auto Workers, Ford was a patronizing tyrant who exploited Black workers to divide the labor movement.

Harry Bennett was Henry Ford’s enforcer, the head of security in the company’s notorious Service Department, described as a thug with a private army of 8,000 spies and goons. He did Ford’s dirty work, especially in fighting unions.

Donald Marshall, a Black former Detroit police officer, was hired by Bennett in 1923 to manage and discipline Black workers at the River Rouge Plant. He would eventually control all hiring of Black workers at Ford and “served as Bennett's eyes and ears, spying on Black workers and their families in order to keep a lid on union activity and enforce discipline.” Willis Ward would have a complicated relationship with Ford, Marshall, and Bennett.

Recruiting Ward to Ford

Henry Ford occasionally attended U-M football games. He was a guest at the 1923 game against the Quantico Marines, which was part of the festivities surrounding the dedication of Yost Field House. Bennett, a former boxer, fancied himself a sportsman and reveled in his association with Kipke and other sports celebrities.

It is unclear when Ford first took a particular interest in Ward, but soon he and Bennett were grooming the young athlete for a career at Ford. They arranged for Ward to get summer jobs at Ford beginning in 1932. During the 1930s, many U-M football players got summer work at Ford through Bennett’s connection with Kipke. Many of the jobs were legitimate, but Bennett sometimes allowed the players to gather for informal practice sessions—a violation of NCAA rules and one factor in Kipke’s firing, in 1937. While many players worked in line and security positions, Ward’s initial job was driving a delivery vehicle, which gave him a view of operations throughout the Rouge Plant. Soon, however, he would be working directly for Donald Marshall.

By some accounts it was Bennett who convinced Ward not to raise a public objection to the Georgia Tech benching, telling the devastated athlete "to remember who your real friends are,” with the implied promise of a job at Ford after graduation.

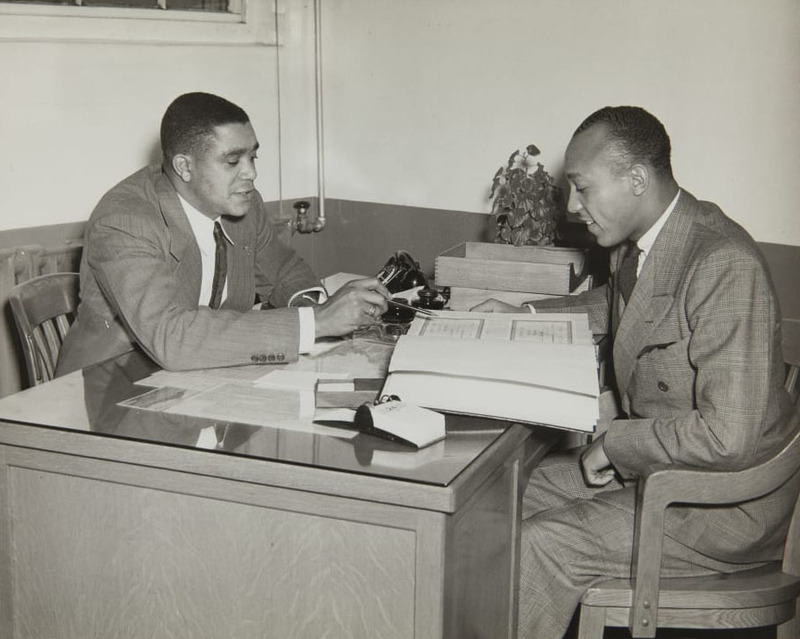

Against the urgings of Bennett and Marshall, Ward registered for U-M Law School in the fall of 1935. Becoming a lawyer had long been an ambition for Ward (and his father). On his registration card, he listed his two contact persons as Eddie Tolan, the former U-M track star from Detroit, and Marshall. After completing his first year of law school, Ward began working full time as Marshall’s assistant in the Negro Division of the Service Department.

Complicated Labor

Ward’s role at Ford, as he saw it, was to help hire and manage the Black workers, prevent or ameliorate racial conflict in the plants, and protect the interests of Black workers—at least as Ward and the company saw them.

By the mid 1930s, Ford employed upwards of 15,000 Black workers, far more than all the other auto companies combined. Although Ford provided genuine opportunities for advancement —to positions in the skilled trades, to foreman, even to lower-level management—the bulk of the Black workforce was concentrated in the lowest-level, dirtiest, most physically demanding and dangerous jobs. The Rouge foundry work force would become overwhelmingly Black. As a college-educated man, Ward was expected to provide a softer touch to managing these workers than the often brutal tactics of Bennett and Marshall.

Others saw his role and that of the Service Department differently—namely, to ensure a compliant workforce, maintain Ford’s reputation and influence in the Black community, and oppose labor union organizing. Ward did receive harsh criticism from pro-labor elements in the national Black press, particularly for his role in a controversy over hiring Black women at the Willow Run bomber plant. It was alleged that Ward had failed to support the Black women out of fear of antagonizing white workers already upset over issues surrounding the Sojourner Truth housing project in Detroit.

As union organizing efforts intensified, Ward and Marshall spoke at a series of meetings around Detroit, sometimes in churches of Ford-friendly ministers, urging support for the company’s opposition to unions. Listeners were reminded of the employment opportunities Ford had provided to African Americans and the support it provided to community organizations.

Rougher tactics were left to others. Ward recalled that during the infamous May 26, 1937, “Battle of the Overpass,” in which Bennett’s thugs brutalized UAW pamphleteers and organizers, “Mr. Bennett told me to stay away from that. He didn’t want me to have any part of that. He wanted to keep me clean, to come back and be able to talk to the employees without any stigma of blood on my hands.”

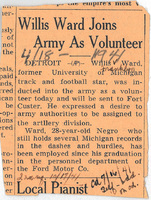

Ward worked for Ford until April 1941, when he was drafted into the U.S. Army—despite the company’s efforts to have him deferred as an indispensable employee in a war production industry. He was discharged in December 1941 because, according to newspaper accounts, he was over the 28-year age limit, and returned to Ford.

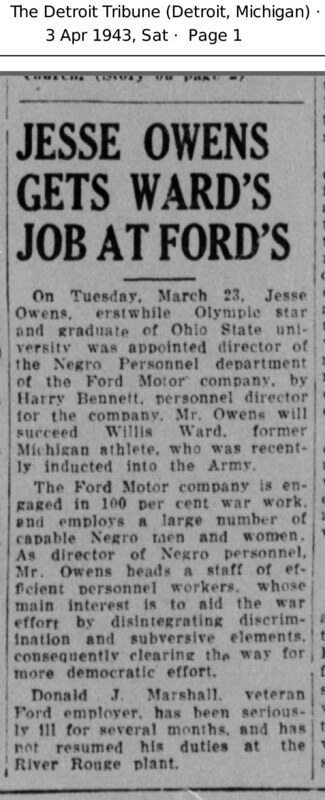

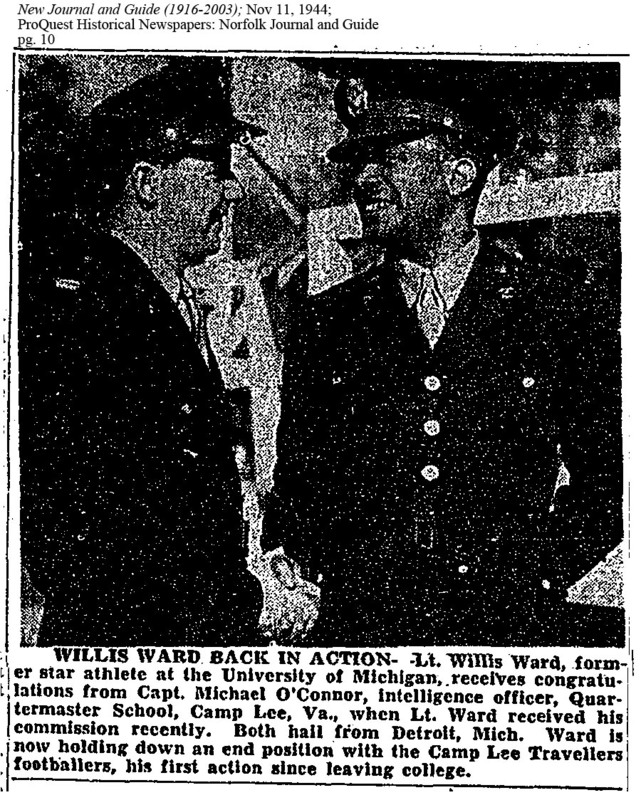

Still eager to serve in the military, Ward was recalled in September 1944 and sent to Officer Candidate School at Camp Lee, Virginia. Ford hired Jesse Owens to fill Ward’s position. After his discharge, Ward returned to his position at Ford; Owens was shunted to a public relations position and soon left the company.

Owens’ work at Ford drew some favorable comment in the Black press, but he apparently never fit in with Bennett's system. Commenting later on Owens' tenure, Bennett said: “Jesse had a lot of ideas. Too many ideas.” As Ward returned to Ford the separate Negro Division of the Personnel Office was abolished, but he continued doing much the same work for the rest of his career with the company.

As Henry Ford's health failed, his grandson Henry II outmaneuvered Bennett to assume control of the company in 1945. He and the family quickly moved to fire Bennett and reconfigure the Personnel and Security divisions through which Bennett had wielded power. Ward, who long since had completed a night-school degree at Detroit College of Law, resigned a little over a year later. He recognized that any power he had to advance or defend the interests of Black workers had rested on his direct access to Bennett.

To the end, Ward was an admirer of Henry Ford and his program to integrate the company’s plants, and was comfortable with the role he had played in it. He recognized the cruder aspects of Bennett’s regime and distanced himself from Marshall when his mentor was accused of using his position to sell jobs. Ward remained convinced that his path of working within the system, leveraging access to power, was more effective than militant opposition as a way to promote and protect the interests of Black workers.

Sources: August Meier and Elliott Rudwick, Black Detroit and the Rise of the UAW, 2007; Beth Tompkins Bates, The Making of Black Detroit in the Age of Henry Ford, 2012; Julia Robinson Harmon, "The Leadership of Robert L. Bradby and the Black Community in East Industrial Detroit," 2006; Willis Ward Alumni File, Bentley Historical Library; Willis Ward Papers, Detroit Public Library; Owen W. Bombard, The Reminiscences of Mr. Willis F. Ward [interview], 1955; Reuther Library-Virtual Motor City, Library of Congress, ProQuest Historical Newspapers.